An in-depth look at the science, and regulation of pesticide products.

PESTICIDES ARE POISONS

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, a professional organization of 67,000 pediatricians dedicated to the health and safety of children, “pesticides are products designed to kill or harm living organisms” and are therefore “inherently toxic.”

Pesticides are poisons by design, and unfortunately the many shortcomings of the EPA’s pesticide registration process means that pesticides are not adequately tested for safety. At the same time, the profitability of the pesticide industry ensures that these chemicals are widely distributed in our environment.

Of the 36 most commonly used lawn care pesticides registered before 1984, only one has purportedly been fully tested and evaluated - sulfur. But in 2017, research from UC Berkeley revealed that even elemental sulfur, the most heavily-used pesticide in California, may in fact harm the respiratory health of children living near farms that use the pesticide.

Health effects of the 36 most commonly used lawn pesticides show that 14 are probable or possible carcinogens, 15 are linked with birth defects, 21 with reproductive effects, 24 with neurotoxicity, 22 with liver or kidney damage, and 34 are sensitizers and/or irritants.

CHILDREN ARE ESPECIALLY VULNERABLE

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2012 report, Pesticide Exposure in Children states, “Epidemiologic evidence demonstrates associations between early life exposure to pesticides and pediatric cancers, decreased cognitive function, and behavioral problems.” The report recommends that government decision-makers create policies which, “Advance less toxic pesticide alternatives.”

Several physical realities make children more vulnerable to environmental toxins than adults, but the EPA does not account for these unique vulnerabilities during the pesticide registration process. According to “Pesticide exposure and child neurodevelopment: summary and implications,” a 2012 paper published by scientists at the University of Pennsylvania:

Young children are particularly vulnerable to toxicants in the environment, including pesticides. The National Research Council’s 1993 report on pesticides in the diets of infants and children recognized that children require a special approach to risk assessment due to their unique vulnerabilities to environmental toxicants, including pesticides (Landrigan, 2011; Landrigan & Goldman, 2011; Landrigan, Kimmel, Correa, & Eskenazi, 2004; Lucas & Allen, 2009; Quiros-Alcala et al., 2011).

Children’s organs are not fully developed until later in life. They continually experience critical periods in development; adverse exposures can cause permanent damage, particularly in utero (Chalupka & Chalupka, 2010). Children’s behaviors and ability to interact with their physical environment change during different stages of growth and development and can place them at greater risk of exposure: children may crawl on the floor, explore objects orally, and play with items they find in the environment (Landrigan et al., 2004). For their weight, children consume more food and drink than adults, increasing their possible dietary exposure; dietary exposure is compounded by children’s immature livers and excretory systems, which may be unable to effectively remove pesticide metabolites (Landrigan et al., 2004). These metabolites may block the absorption of critical nutrients in children’s diets, which further affects health outcomes. Potential routes of exposure to pesticides include in utero or through breast milk, via ingestion of food contaminated with pesticides, and household exposures via dermal contact (Chalupka & Chalupka, 2010). Children live closer to the ground than adults, which may increase their exposure to pesticides sprayed or precipitated there (Paulson & Barnett, 2010).

Furthermore, leukemia rates are consistently elevated among among children whose parents used pesticides in the home or garden, among children of pesticide applicators and among children who grow up on farms.

A study in Cancer Causes and Control suggests that preconception pesticide exposure and possible exposure during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of childhood brain tumors.

PESTICIDES ARE NOT EFFECTIVELY SCREENED FOR SAFETY

Any pesticide legally used in the United States must be registered with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This registration does not constitute an approval rating or safety claim of any sort, nor does it guarantee that the chemicals have been fully tested for environmental and human health effects.

The primary federal laws that govern how EPA regulates pesticides in the United States are Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). FIFRA was last significantly updated in 1972, and has been subject to major pesticide industry and farm lobby influence.

The Center for Biological Diversity and Pesticide Action Network North America summarize FIFRA’s shortcomings this way:

FIFRA is fundamentally a licensing law with consumer-protection origins administered by the EPA. The ability to regulate pesticide use under FIFRA is very limited. Unlike other environmental statutes, FIFRA does not establish a permitting system for pesticide use. No approval is required prior to using a pesticide, and the law affords no localized decision-making mechanisms. FIFRA’s regulation of pesticide “use” is achieved instead through labeling restrictions.

The pesticide industry has subverted the intended protections of FIFRA, and the statute remains subject to intensive lobbying by pesticide interests. Chemical corporations conduct the science, which often escapes peer review and public scrutiny under the veil of “confidential business information.” FIFRA has multiple mechanisms for allowing pesticide manufacturers to delay any actions that would remove their products from the market. The EPA cannot act quickly and independently to pull known hazardous products from the market. FIFRA delegates enforcement to the states, which are poorly funded to do enforcement. Enforcement of mitigation measures that are on pesticide labels rarely occurs, even for the most toxic pesticides.

Pesticides lacking data on health and environmental effects since 1972 (and in use for much longer) are still registered, although the required toxicity studies have yet to be performed/submitted. A 2019 study published in Environmental Health found:

There are 72, 17, and 11 pesticides approved for outdoor agricultural applications in the USA that are banned or in the process of complete phase out in the EU, Brazil, and China, respectively. Of the pesticides used in USA agriculture in 2016, 322 million pounds were of pesticides banned in the EU, 26 million pounds were of pesticides banned in Brazil and 40 million pounds were of pesticides banned in China. Pesticides banned in the EU account for more than a quarter of all agricultural pesticide use in the USA. The majority of pesticides banned in at least two of these three nations have not appreciably decreased in the USA over the last 25 years and almost all have stayed constant or increased over the last 10 years.

Scandals surrounding two pesticide testing laboratories revealed that fraudulent data had been submitted -- data that are still considered valid in the involved pesticides' registrations. And yet, EPA's evaluation process is considered a legitimate indicator of a pesticides' acceptability, continually allowing carcinogens to be deliberately introduced into our environment.

What level of risk is reasonable in the name of cosmetic landscaping? We believe the risks associated with human exposure to conventional pesticides for cosmetic purposes outweigh their benefits, particularly when a healthy, beautiful landscape can be attained without them.

Furthermore, conventional fertilizers, pesticides and landscaping practices create greenhouse gasses that drive climate change. By adopting organic practices, communities can reduce their carbon footprint, which is a growing priority for many.

HEALTH EFFECTS AND ECONOMIC BENEFIT ARE CONSIDERED EQUALLY

Under FIFRA, pesticide use relies on a risk-benefit statute, which allows the use of pesticides with known hazards based on the judgment that various levels of risk are acceptable. However, EPA, who performs this risk assessment, assumes that a pesticide would not be marketed if there were no benefits to using it and therefore no risk/benefit analysis is done "up front."

Human health is only one of several factors considered in the pesticide registration process, as an EPA guide for evaluating pesticides explains, “Pursuant to FIFRA sections 2(bb) and 3(c)(5), the Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) considers the “economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of any pesticide” when registering new pesticides.”

A troubling example of the effects of this decision-making structure is chlorpyrifos, a pesticide widely used in agriculture. Decades of research have demonstrated that even small amounts of exposure can cause permanent health damage to babies and children. An article by Harvard University researchers explains:

In March 2017, despite mounting evidence for its toxicity, Scott Pruitt, head of the EPA under President Donald Trump, denied the petition from the two NGOs and decided not to ban chlorpyrifos. This decision would leave chlorpyrifos on the market until... 2022. In their press release, the EPA acknowledged that current use of chlorpyrifos leads to its incorporation in food and drinking water above safe levels, but they emphasized that chlorpyrifos was a highly effective and widely used pest-management tool. A unilateral ban in the U.S. would disrupt international trading and hurt American farmers and consumers financially.

FALSE SAFETY CLAIMS AND LITTLE ENFORCEMENT

The pesticide industry has a long-standing track record of misleading consumers about the potential dangers associated with the use of their products. The U.S. General Accounting Office , and the New York and Pennsylvania Attorneys General have charged and successfully prosecuted various pesticide manufacturers and distributors with misleading advertising and prohibited safety claims.

EPA’s website includes numerous accounts of civil federal pesticide law violations for improper safety instructions on packaging. These practices continue today with manufacturers and distributors commonly asserting their products are safe for pets and children.

Seasoned EPA prosecutors say FIFRA needs stronger criminal penalties like those provided under the other major federal environmental laws. In a paper published in 2017 titled, “FIFRA at 40: The Need for Felonies for Pesticide Crimes,” two experienced EPA prosecutors explained that a series of incidents and criminal prosecutions, "demonstrate the inability of misdemeanor penalties to effectively deter pesticide crimes.”

The strongest FIFRA penalty is designed to protect pesticide manufacturers, not the people who are harmed by their products. As the EPA prosecutors explain, “FIFRA contains only one felony penalty, applicable to ‘[a]ny person, who, with intent to defraud, uses or reveals information relative to formulas of products’ that is acquired during the registration process.” (7 U .S .C . §136l(b)(3)) The penalty for such a crime is up to $10,000 and/or up to three years in prison. In contrast, the maximum prison time for a “private applicator or other person” who knowingly uses a pesticide to cause death or injury is 30 days.

In 2016, U.S. District Judge Jose Martinez lamented the fact that FIFRA’s maximum sentence was one year in prison for two defendants whose knowing, illegal application of pesticides had permanently injured a nine-year-old boy. Because the defendants were commercial pesticide applicators, they received the maximum one year sentence, but if either had been deemed a “private applicator or other person,” their maximum sentence would have been 30 days.

In terms of financial penalties, the EPA prosecutors explain, “FIFRA’s current authorization of only up to $1,000 in fines for private applicators is unique among the federal environmental statutes, and is likely to signal to prosecutors and judges that such pesticide crimes are not serious offenses.”

PESTICIDES ARE BIG BUSINESS

U.S. expenditures for conventional pesticides totalled nearly $14 billion in 2012 according to EPA's Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage report, providing significant financial incentive to the industry to maintain the existing regulatory structure.

THE UNKNOWN TOXICITY OF INERT PESTICIDE INGREDIENTS

Most people don’t know that the safety of emulsifiers, solvents and other “inert” pesticide ingredients are not assessed or considered in the pesticide registration process. With few exceptions, pesticide manufacturers disclose only the identity of “active ingredients,” which generally comprise only a minor portion of pesticide products. The identity of other ingredients are considered confidential or trade secrets.

A 2010 study in Environmental Management demonstrated that when inert ingredients are identified and assessed by the same process as the active ingredient, the product-specific risk can be much greater than that calculated for the active ingredient alone.

A comprehensive review of gaps in risk assessments for adjuvants in pesticide formulations was conducted in 2018 by scientists at King’s College London and published in Frontiers in Public Health. The review concluded that ignoring the potential dangers of these ingredients in commonly used commercial pesticides leads to inaccuracies in the safety profile of the pesticide solution, as well as confusion in scientific literature on pesticide effects. The review suggests that new regulations are needed to protect people and the environment from toxic pesticide ingredients.

This summary of the 2018 study appeared in ScienceDaily:

"Exposure to environmental levels of some of these adjuvant mixtures can affect non-target organisms -- and even can cause chronic human disease," says Dr Robin Mesnage from King's College London, who co-wrote the review with Dr Michael Antoniou. "Despite this, adjuvants are not currently subject to an acceptable daily intake and are not included in the health risk assessment of dietary exposures to pesticide residues."

Pesticides are a mixture of chemicals made up of an active ingredient -- the substance that kills or repels a pest -- along with a mixture of other ingredients that help with the application or function of the active ingredient. These other ingredients are known as adjuvants, and include dyes, anti-foaming agents and surfactants.

Regulatory tests for pesticide safety are currently only done on the active ingredient, which assumes the other ingredients have no effects. This means the full toxicity of a pesticide formulation -- including those used in both agriculture and domestic gardens -- is not shown.

"Currently, the health risk assessment of pesticides in the European Union and in the United States focuses almost exclusively on the active ingredient," explains Dr Mesnage. "Despite the known toxicity of adjuvants, they are regulated differently from active principles, with their toxic effects being generally ignored."

Based on a review of current pesticide literature, the authors describe how unregulated chemicals present in commercial formulations of pesticides could provide a missing link between pesticide exposure and observed negative outcomes.

The researchers focused on glyphosate-based herbicides, the most used pesticide worldwide. They point out that this weed killer has so many different adjuvant formulations that a safety test of one weed killer does not test the safety of another.

"Studies comparing the toxicity of commercial weed-killer formulations to that of glyphosate alone have shown that several formulations are up to 1,000 times more toxic than glyphosate on human cells. We believe that the adjuvants are responsible for this additional toxic effect," says Dr Mesnage.

"Testing of whole pesticide formulations instead of just active ingredients alone would create a precautionary approach, ensuring that the guidance value for the pesticide is valid for the worst-case exposure scenario," says Dr Mesnage.

EPA IGNORES LONG-TERM HEALTH EFFECTS AND LOW-DOSE EXPOSURE

EPA and FDA’s health risk assessments are designed to prevent acute poisoning and other observable effects in test subjects, but do not consider long-term effects, such as whether a child will develop cancer 20 years after exposure. In fact, they ignore those long-term effects.

The journal Environmental Health Perspectives explained the process for toxicity assessment as follows:

Since the 1920s, the most common method for testing a chemical for its acute oral toxicity after a single exposure has been to "feed" it (by oral gavage) in different amounts to groups of rats and then do a body count. This test is called the LD50, for lethal dose 50% - the dose at which half of the rats died.

A 2018 paper published in Frontiers in Public Health mentioned above affirms that description and includes more information on how doses are extrapolated from rodent test subjects to humans.

The ADI [acceptable daily intake] for a given pesticide active ingredient is derived from laboratory animal experiments performed by industry in support of regulatory approval. The objective of these experiments is to ascertain the dose of the chemical that results in a no observed adverse effect in the animals. Once this “no observed adverse effect level” is defined for the chemical in question, it is divided by a predetermined value to account for uncertainty factors and thus provide a greater margin of safety. Typically, a factor of 10 is applied for animal to human extrapolation and another factor of 10 for inter-individual variability in the human population.

LOW DOSES IMPACT HEALTH

EPA’s focus on short-term effects of high doses is not supported by science. A 2012 study published in Endocrine Reviews titled “Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses” concludes that:

Whether low doses of EDCs influence certain human disorders is no longer conjecture, because epidemiological studies show that environmental exposures to EDCs are associated with human diseases and disabilities. We conclude that when nonmonotonic dose-response curves occur, the effects of low doses cannot be predicted by the effects observed at high doses. Thus, fundamental changes in chemical testing and safety determination are needed to protect human health.

Many studies have been published in recent years demonstrating the harmful effects that pesticides have on human health, even at very low doses.

One example is chlorpyrifos, a pesticide mentioned above. Introduced by Dow Chemical in 1965, chlorpyrifos is the most widely-used pesticide on crops, and is also widely used in non-agricultural settings like golf courses. According to Theodore Slotkin, a scientist at Duke University Medical Center, who has published dozens of studies on rats exposed to chlorpyrifos shortly after birth, “Even at exquisitely low doses, this compound would stop cells from dividing and push them instead into programmed cell death.”

A New York Times article explained Slotkin’s research in 2017:

In the animal studies, Dr. Slotkin was able to demonstrate a clear cause-and effect relationship. It didn’t matter when the young rats were exposed; their developing brains were vulnerable to its effects throughout gestation and early childhood, and exposure led to structural abnormalities, behavioral problems, impaired cognitive performance and depressive-like symptoms.

An article from Harvard University explains that research demonstrating that chlorpyrifos harms developing brains at low doses or over the long-term is not considered in regulatory decision-making:

Most of Dow Chemical’s studies relied on standard toxicity testing recommended in the “OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals.” However, these methods cannot detect the more subtle effects caused by low doses and long-term exposures. Effects of chlorpyrifos on brain development are the focus of many academic research articles but not included in OECD guidelines. Therefore, these academic studies were not originally considered in regulatory decision making.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international organization of most industrialized nations which maintain comprehensive testing requirements for pesticides and industrial chemicals. EPA says that their test guidelines are harmonized with OECD’s in part to “reduce the burden on chemical producers.”

Experiments conducted to assess the effects of Roundup, aka glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide, on human embryonic and placental cells illustrated that a dose of Roundup as small as 0.01% resulted in a reduction of 19% of estrogen production, a necessary process for normal fetal development.

SYNERGISTIC EFFECTS OF MULTIPLE PESTICIDES NOT CONSIDERED

The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety defines synergism as "the effect caused when exposure to two or more chemicals at one time results in health effects that are greater than the sum of the effects of the individual chemicals."

The registration process only requires testing of active ingredients singly, not taking into account real world exposures to multiple chemicals in formulated pesticide products at one time.

PESTICIDE MANUFACTURERS CONDUCT THEIR OWN SAFETY TESTING

Pesticide toxicity tests are typically conducted or funded by a pesticide's manufacturer, which have little to no incentive to ensure the safety of their products, creating a clear conflict of interest (COI). Pesticide Regulation amid the Influence of Industry, a study published created by 15 scientists and published in the journal BioScience in 2014 explains:

“In many studies, the effects of funding source on research outcomes have been quantified, and it has been shown that industry-supplied studies are more likely to support effects favorable to industry.”

“COIs are currently ingrained in the process, because the companies registering chemicals are required to supply data involved in risk review (USEPA 2008). Furthermore, the USEPA works with industry to establish the methodology and experimental design for studies. The complexity and logistics of these designs can make them prohibitively expensive for researchers outside of industry, often leaving industry as the only entity that can afford to conduct the research to the USEPA's specifications or that is knowledgeable of the requirements. Therefore, all or most of the data used in risk assessments may come from industry-supplied research, despite clear COIs.”

The paper goes on to explain how industry involvement in the risk assessments compromises research findings:

“In many studies, the effects of funding source on research outcomes have been quantified, and it has been shown that industry-supplied studies are more likely to support effects favorable to industry. For instance, the best predictor of whether the herbicide atrazine had significant biological effects in a study was the funding source, with manufacturer-funded research having a greater likelihood of finding no effect or only small effects (Hayes 2004).... Because of potential or real biases, industry-supplied studies can obscure the real impact of a pesticide, which may result in a sluggish regulatory process most advantageous to manufacturers (Michaels 2008, Rohr and McCoy 2010a).”

Atrazine, the pesticide mentioned in the passage above has been shown to cause castration (demasculinization) and feminization of amphibians at extremely low concentrations in the laboratory and in the wild. Atrazine was banned in the European Union more than a decade ago.

University of California professor of Integrative Biology Tyrone Hayes described the impact of atrazine’s widespread use in a paper published in the journal BioScience in 2004 There Is No Denying This: Defusing the Confusion about Atrazine.

"Years have passed since DDT was banned in the United States, but it is unclear how much policymakers and the public have learned from the case of this dangerous pesticide. DDT was banned on the basis of even less scientific evidence than currently exists for the negative impacts of atrazine. Atrazine, an herbicide, is the top-selling product for the largest chemical company in the world. Its primary consumer (the United States) boasts the largest economy in the world, and it is used on corn, the largest crop in the United States. One of the primary targets for atrazine is the weed common groundsel (Senecio vulgaris), the most widespread botanical in the world (Kadereit 1984). As a result of its frequent use, atrazine is the most common contaminant of ground, surface, and drinking water (Aspelin 1994), and its use over the last 40 years has resulted in the evolution of more herbicide-resistant weeds (> 60 species) than any other herbicide (Heap 1997, Gadamski et al. 2003)."

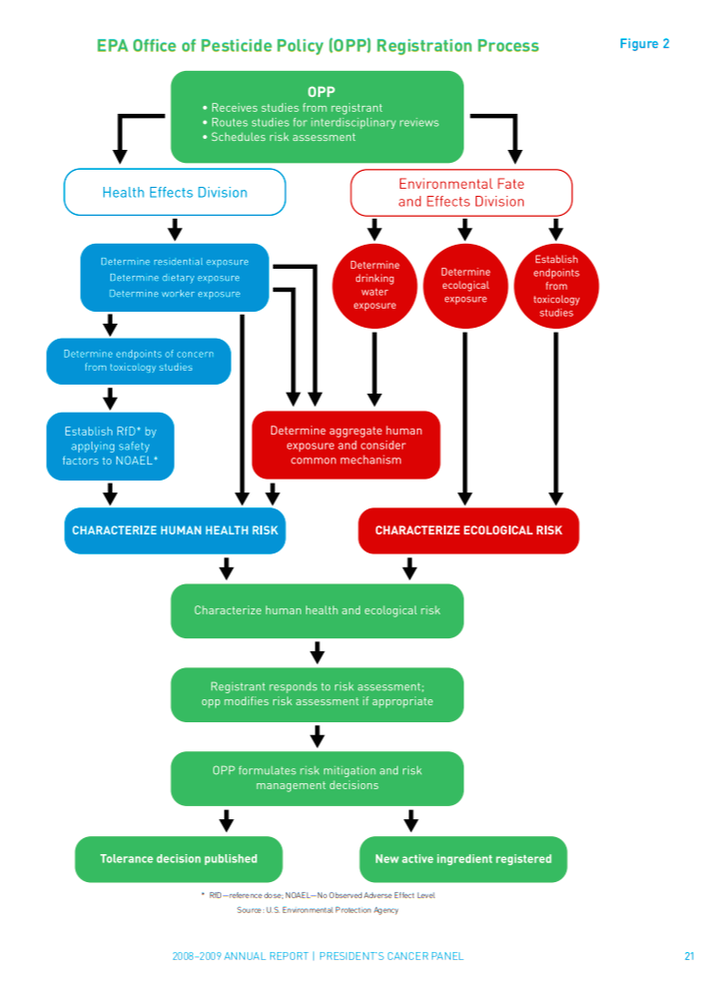

The flowchart below illustrates the EPA registration (approval) process for a new pesticide or a previously registered pesticide having a new ingredient or proposed new use. It appears in the National Institutes of Health 2010 report President’s Cancer Panel-Reports. Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk: What We Can Do Now. Note that the first step in the registration process is “Receives studies from the registrant.”

PESTICIDES ARE POISONS

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, a professional organization of 67,000 pediatricians dedicated to the health and safety of children, “pesticides are products designed to kill or harm living organisms” and are therefore “inherently toxic.”

Pesticides are poisons by design, and unfortunately the many shortcomings of the EPA’s pesticide registration process means that pesticides are not adequately tested for safety. At the same time, the profitability of the pesticide industry ensures that these chemicals are widely distributed in our environment.

Of the 36 most commonly used lawn care pesticides registered before 1984, only one has purportedly been fully tested and evaluated - sulfur. But in 2017, research from UC Berkeley revealed that even elemental sulfur, the most heavily-used pesticide in California, may in fact harm the respiratory health of children living near farms that use the pesticide.

Health effects of the 36 most commonly used lawn pesticides show that 14 are probable or possible carcinogens, 15 are linked with birth defects, 21 with reproductive effects, 24 with neurotoxicity, 22 with liver or kidney damage, and 34 are sensitizers and/or irritants.

CHILDREN ARE ESPECIALLY VULNERABLE

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2012 report, Pesticide Exposure in Children states, “Epidemiologic evidence demonstrates associations between early life exposure to pesticides and pediatric cancers, decreased cognitive function, and behavioral problems.” The report recommends that government decision-makers create policies which, “Advance less toxic pesticide alternatives.”

Several physical realities make children more vulnerable to environmental toxins than adults, but the EPA does not account for these unique vulnerabilities during the pesticide registration process. According to “Pesticide exposure and child neurodevelopment: summary and implications,” a 2012 paper published by scientists at the University of Pennsylvania:

Young children are particularly vulnerable to toxicants in the environment, including pesticides. The National Research Council’s 1993 report on pesticides in the diets of infants and children recognized that children require a special approach to risk assessment due to their unique vulnerabilities to environmental toxicants, including pesticides (Landrigan, 2011; Landrigan & Goldman, 2011; Landrigan, Kimmel, Correa, & Eskenazi, 2004; Lucas & Allen, 2009; Quiros-Alcala et al., 2011).

Children’s organs are not fully developed until later in life. They continually experience critical periods in development; adverse exposures can cause permanent damage, particularly in utero (Chalupka & Chalupka, 2010). Children’s behaviors and ability to interact with their physical environment change during different stages of growth and development and can place them at greater risk of exposure: children may crawl on the floor, explore objects orally, and play with items they find in the environment (Landrigan et al., 2004). For their weight, children consume more food and drink than adults, increasing their possible dietary exposure; dietary exposure is compounded by children’s immature livers and excretory systems, which may be unable to effectively remove pesticide metabolites (Landrigan et al., 2004). These metabolites may block the absorption of critical nutrients in children’s diets, which further affects health outcomes. Potential routes of exposure to pesticides include in utero or through breast milk, via ingestion of food contaminated with pesticides, and household exposures via dermal contact (Chalupka & Chalupka, 2010). Children live closer to the ground than adults, which may increase their exposure to pesticides sprayed or precipitated there (Paulson & Barnett, 2010).

Furthermore, leukemia rates are consistently elevated among among children whose parents used pesticides in the home or garden, among children of pesticide applicators and among children who grow up on farms.

A study in Cancer Causes and Control suggests that preconception pesticide exposure and possible exposure during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of childhood brain tumors.

PESTICIDES ARE NOT EFFECTIVELY SCREENED FOR SAFETY

Any pesticide legally used in the United States must be registered with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This registration does not constitute an approval rating or safety claim of any sort, nor does it guarantee that the chemicals have been fully tested for environmental and human health effects.

The primary federal laws that govern how EPA regulates pesticides in the United States are Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). FIFRA was last significantly updated in 1972, and has been subject to major pesticide industry and farm lobby influence.

The Center for Biological Diversity and Pesticide Action Network North America summarize FIFRA’s shortcomings this way:

FIFRA is fundamentally a licensing law with consumer-protection origins administered by the EPA. The ability to regulate pesticide use under FIFRA is very limited. Unlike other environmental statutes, FIFRA does not establish a permitting system for pesticide use. No approval is required prior to using a pesticide, and the law affords no localized decision-making mechanisms. FIFRA’s regulation of pesticide “use” is achieved instead through labeling restrictions.

The pesticide industry has subverted the intended protections of FIFRA, and the statute remains subject to intensive lobbying by pesticide interests. Chemical corporations conduct the science, which often escapes peer review and public scrutiny under the veil of “confidential business information.” FIFRA has multiple mechanisms for allowing pesticide manufacturers to delay any actions that would remove their products from the market. The EPA cannot act quickly and independently to pull known hazardous products from the market. FIFRA delegates enforcement to the states, which are poorly funded to do enforcement. Enforcement of mitigation measures that are on pesticide labels rarely occurs, even for the most toxic pesticides.

Pesticides lacking data on health and environmental effects since 1972 (and in use for much longer) are still registered, although the required toxicity studies have yet to be performed/submitted. A 2019 study published in Environmental Health found:

There are 72, 17, and 11 pesticides approved for outdoor agricultural applications in the USA that are banned or in the process of complete phase out in the EU, Brazil, and China, respectively. Of the pesticides used in USA agriculture in 2016, 322 million pounds were of pesticides banned in the EU, 26 million pounds were of pesticides banned in Brazil and 40 million pounds were of pesticides banned in China. Pesticides banned in the EU account for more than a quarter of all agricultural pesticide use in the USA. The majority of pesticides banned in at least two of these three nations have not appreciably decreased in the USA over the last 25 years and almost all have stayed constant or increased over the last 10 years.

Scandals surrounding two pesticide testing laboratories revealed that fraudulent data had been submitted -- data that are still considered valid in the involved pesticides' registrations. And yet, EPA's evaluation process is considered a legitimate indicator of a pesticides' acceptability, continually allowing carcinogens to be deliberately introduced into our environment.

What level of risk is reasonable in the name of cosmetic landscaping? We believe the risks associated with human exposure to conventional pesticides for cosmetic purposes outweigh their benefits, particularly when a healthy, beautiful landscape can be attained without them.

Furthermore, conventional fertilizers, pesticides and landscaping practices create greenhouse gasses that drive climate change. By adopting organic practices, communities can reduce their carbon footprint, which is a growing priority for many.

HEALTH EFFECTS AND ECONOMIC BENEFIT ARE CONSIDERED EQUALLY

Under FIFRA, pesticide use relies on a risk-benefit statute, which allows the use of pesticides with known hazards based on the judgment that various levels of risk are acceptable. However, EPA, who performs this risk assessment, assumes that a pesticide would not be marketed if there were no benefits to using it and therefore no risk/benefit analysis is done "up front."

Human health is only one of several factors considered in the pesticide registration process, as an EPA guide for evaluating pesticides explains, “Pursuant to FIFRA sections 2(bb) and 3(c)(5), the Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) considers the “economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of any pesticide” when registering new pesticides.”

A troubling example of the effects of this decision-making structure is chlorpyrifos, a pesticide widely used in agriculture. Decades of research have demonstrated that even small amounts of exposure can cause permanent health damage to babies and children. An article by Harvard University researchers explains:

In March 2017, despite mounting evidence for its toxicity, Scott Pruitt, head of the EPA under President Donald Trump, denied the petition from the two NGOs and decided not to ban chlorpyrifos. This decision would leave chlorpyrifos on the market until... 2022. In their press release, the EPA acknowledged that current use of chlorpyrifos leads to its incorporation in food and drinking water above safe levels, but they emphasized that chlorpyrifos was a highly effective and widely used pest-management tool. A unilateral ban in the U.S. would disrupt international trading and hurt American farmers and consumers financially.

FALSE SAFETY CLAIMS AND LITTLE ENFORCEMENT

The pesticide industry has a long-standing track record of misleading consumers about the potential dangers associated with the use of their products. The U.S. General Accounting Office , and the New York and Pennsylvania Attorneys General have charged and successfully prosecuted various pesticide manufacturers and distributors with misleading advertising and prohibited safety claims.

EPA’s website includes numerous accounts of civil federal pesticide law violations for improper safety instructions on packaging. These practices continue today with manufacturers and distributors commonly asserting their products are safe for pets and children.

Seasoned EPA prosecutors say FIFRA needs stronger criminal penalties like those provided under the other major federal environmental laws. In a paper published in 2017 titled, “FIFRA at 40: The Need for Felonies for Pesticide Crimes,” two experienced EPA prosecutors explained that a series of incidents and criminal prosecutions, "demonstrate the inability of misdemeanor penalties to effectively deter pesticide crimes.”

The strongest FIFRA penalty is designed to protect pesticide manufacturers, not the people who are harmed by their products. As the EPA prosecutors explain, “FIFRA contains only one felony penalty, applicable to ‘[a]ny person, who, with intent to defraud, uses or reveals information relative to formulas of products’ that is acquired during the registration process.” (7 U .S .C . §136l(b)(3)) The penalty for such a crime is up to $10,000 and/or up to three years in prison. In contrast, the maximum prison time for a “private applicator or other person” who knowingly uses a pesticide to cause death or injury is 30 days.

In 2016, U.S. District Judge Jose Martinez lamented the fact that FIFRA’s maximum sentence was one year in prison for two defendants whose knowing, illegal application of pesticides had permanently injured a nine-year-old boy. Because the defendants were commercial pesticide applicators, they received the maximum one year sentence, but if either had been deemed a “private applicator or other person,” their maximum sentence would have been 30 days.

In terms of financial penalties, the EPA prosecutors explain, “FIFRA’s current authorization of only up to $1,000 in fines for private applicators is unique among the federal environmental statutes, and is likely to signal to prosecutors and judges that such pesticide crimes are not serious offenses.”

PESTICIDES ARE BIG BUSINESS

U.S. expenditures for conventional pesticides totalled nearly $14 billion in 2012 according to EPA's Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage report, providing significant financial incentive to the industry to maintain the existing regulatory structure.

THE UNKNOWN TOXICITY OF INERT PESTICIDE INGREDIENTS

Most people don’t know that the safety of emulsifiers, solvents and other “inert” pesticide ingredients are not assessed or considered in the pesticide registration process. With few exceptions, pesticide manufacturers disclose only the identity of “active ingredients,” which generally comprise only a minor portion of pesticide products. The identity of other ingredients are considered confidential or trade secrets.

A 2010 study in Environmental Management demonstrated that when inert ingredients are identified and assessed by the same process as the active ingredient, the product-specific risk can be much greater than that calculated for the active ingredient alone.

A comprehensive review of gaps in risk assessments for adjuvants in pesticide formulations was conducted in 2018 by scientists at King’s College London and published in Frontiers in Public Health. The review concluded that ignoring the potential dangers of these ingredients in commonly used commercial pesticides leads to inaccuracies in the safety profile of the pesticide solution, as well as confusion in scientific literature on pesticide effects. The review suggests that new regulations are needed to protect people and the environment from toxic pesticide ingredients.

This summary of the 2018 study appeared in ScienceDaily:

"Exposure to environmental levels of some of these adjuvant mixtures can affect non-target organisms -- and even can cause chronic human disease," says Dr Robin Mesnage from King's College London, who co-wrote the review with Dr Michael Antoniou. "Despite this, adjuvants are not currently subject to an acceptable daily intake and are not included in the health risk assessment of dietary exposures to pesticide residues."

Pesticides are a mixture of chemicals made up of an active ingredient -- the substance that kills or repels a pest -- along with a mixture of other ingredients that help with the application or function of the active ingredient. These other ingredients are known as adjuvants, and include dyes, anti-foaming agents and surfactants.

Regulatory tests for pesticide safety are currently only done on the active ingredient, which assumes the other ingredients have no effects. This means the full toxicity of a pesticide formulation -- including those used in both agriculture and domestic gardens -- is not shown.

"Currently, the health risk assessment of pesticides in the European Union and in the United States focuses almost exclusively on the active ingredient," explains Dr Mesnage. "Despite the known toxicity of adjuvants, they are regulated differently from active principles, with their toxic effects being generally ignored."

Based on a review of current pesticide literature, the authors describe how unregulated chemicals present in commercial formulations of pesticides could provide a missing link between pesticide exposure and observed negative outcomes.

The researchers focused on glyphosate-based herbicides, the most used pesticide worldwide. They point out that this weed killer has so many different adjuvant formulations that a safety test of one weed killer does not test the safety of another.

"Studies comparing the toxicity of commercial weed-killer formulations to that of glyphosate alone have shown that several formulations are up to 1,000 times more toxic than glyphosate on human cells. We believe that the adjuvants are responsible for this additional toxic effect," says Dr Mesnage.

"Testing of whole pesticide formulations instead of just active ingredients alone would create a precautionary approach, ensuring that the guidance value for the pesticide is valid for the worst-case exposure scenario," says Dr Mesnage.

EPA IGNORES LONG-TERM HEALTH EFFECTS AND LOW-DOSE EXPOSURE

EPA and FDA’s health risk assessments are designed to prevent acute poisoning and other observable effects in test subjects, but do not consider long-term effects, such as whether a child will develop cancer 20 years after exposure. In fact, they ignore those long-term effects.

The journal Environmental Health Perspectives explained the process for toxicity assessment as follows:

Since the 1920s, the most common method for testing a chemical for its acute oral toxicity after a single exposure has been to "feed" it (by oral gavage) in different amounts to groups of rats and then do a body count. This test is called the LD50, for lethal dose 50% - the dose at which half of the rats died.

A 2018 paper published in Frontiers in Public Health mentioned above affirms that description and includes more information on how doses are extrapolated from rodent test subjects to humans.

The ADI [acceptable daily intake] for a given pesticide active ingredient is derived from laboratory animal experiments performed by industry in support of regulatory approval. The objective of these experiments is to ascertain the dose of the chemical that results in a no observed adverse effect in the animals. Once this “no observed adverse effect level” is defined for the chemical in question, it is divided by a predetermined value to account for uncertainty factors and thus provide a greater margin of safety. Typically, a factor of 10 is applied for animal to human extrapolation and another factor of 10 for inter-individual variability in the human population.

LOW DOSES IMPACT HEALTH

EPA’s focus on short-term effects of high doses is not supported by science. A 2012 study published in Endocrine Reviews titled “Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses” concludes that:

Whether low doses of EDCs influence certain human disorders is no longer conjecture, because epidemiological studies show that environmental exposures to EDCs are associated with human diseases and disabilities. We conclude that when nonmonotonic dose-response curves occur, the effects of low doses cannot be predicted by the effects observed at high doses. Thus, fundamental changes in chemical testing and safety determination are needed to protect human health.

Many studies have been published in recent years demonstrating the harmful effects that pesticides have on human health, even at very low doses.

One example is chlorpyrifos, a pesticide mentioned above. Introduced by Dow Chemical in 1965, chlorpyrifos is the most widely-used pesticide on crops, and is also widely used in non-agricultural settings like golf courses. According to Theodore Slotkin, a scientist at Duke University Medical Center, who has published dozens of studies on rats exposed to chlorpyrifos shortly after birth, “Even at exquisitely low doses, this compound would stop cells from dividing and push them instead into programmed cell death.”

A New York Times article explained Slotkin’s research in 2017:

In the animal studies, Dr. Slotkin was able to demonstrate a clear cause-and effect relationship. It didn’t matter when the young rats were exposed; their developing brains were vulnerable to its effects throughout gestation and early childhood, and exposure led to structural abnormalities, behavioral problems, impaired cognitive performance and depressive-like symptoms.

An article from Harvard University explains that research demonstrating that chlorpyrifos harms developing brains at low doses or over the long-term is not considered in regulatory decision-making:

Most of Dow Chemical’s studies relied on standard toxicity testing recommended in the “OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals.” However, these methods cannot detect the more subtle effects caused by low doses and long-term exposures. Effects of chlorpyrifos on brain development are the focus of many academic research articles but not included in OECD guidelines. Therefore, these academic studies were not originally considered in regulatory decision making.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international organization of most industrialized nations which maintain comprehensive testing requirements for pesticides and industrial chemicals. EPA says that their test guidelines are harmonized with OECD’s in part to “reduce the burden on chemical producers.”

Experiments conducted to assess the effects of Roundup, aka glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide, on human embryonic and placental cells illustrated that a dose of Roundup as small as 0.01% resulted in a reduction of 19% of estrogen production, a necessary process for normal fetal development.

SYNERGISTIC EFFECTS OF MULTIPLE PESTICIDES NOT CONSIDERED

The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety defines synergism as "the effect caused when exposure to two or more chemicals at one time results in health effects that are greater than the sum of the effects of the individual chemicals."

The registration process only requires testing of active ingredients singly, not taking into account real world exposures to multiple chemicals in formulated pesticide products at one time.

PESTICIDE MANUFACTURERS CONDUCT THEIR OWN SAFETY TESTING

Pesticide toxicity tests are typically conducted or funded by a pesticide's manufacturer, which have little to no incentive to ensure the safety of their products, creating a clear conflict of interest (COI). Pesticide Regulation amid the Influence of Industry, a study published created by 15 scientists and published in the journal BioScience in 2014 explains:

“In many studies, the effects of funding source on research outcomes have been quantified, and it has been shown that industry-supplied studies are more likely to support effects favorable to industry.”

“COIs are currently ingrained in the process, because the companies registering chemicals are required to supply data involved in risk review (USEPA 2008). Furthermore, the USEPA works with industry to establish the methodology and experimental design for studies. The complexity and logistics of these designs can make them prohibitively expensive for researchers outside of industry, often leaving industry as the only entity that can afford to conduct the research to the USEPA's specifications or that is knowledgeable of the requirements. Therefore, all or most of the data used in risk assessments may come from industry-supplied research, despite clear COIs.”

The paper goes on to explain how industry involvement in the risk assessments compromises research findings:

“In many studies, the effects of funding source on research outcomes have been quantified, and it has been shown that industry-supplied studies are more likely to support effects favorable to industry. For instance, the best predictor of whether the herbicide atrazine had significant biological effects in a study was the funding source, with manufacturer-funded research having a greater likelihood of finding no effect or only small effects (Hayes 2004).... Because of potential or real biases, industry-supplied studies can obscure the real impact of a pesticide, which may result in a sluggish regulatory process most advantageous to manufacturers (Michaels 2008, Rohr and McCoy 2010a).”

Atrazine, the pesticide mentioned in the passage above has been shown to cause castration (demasculinization) and feminization of amphibians at extremely low concentrations in the laboratory and in the wild. Atrazine was banned in the European Union more than a decade ago.

University of California professor of Integrative Biology Tyrone Hayes described the impact of atrazine’s widespread use in a paper published in the journal BioScience in 2004 There Is No Denying This: Defusing the Confusion about Atrazine.

"Years have passed since DDT was banned in the United States, but it is unclear how much policymakers and the public have learned from the case of this dangerous pesticide. DDT was banned on the basis of even less scientific evidence than currently exists for the negative impacts of atrazine. Atrazine, an herbicide, is the top-selling product for the largest chemical company in the world. Its primary consumer (the United States) boasts the largest economy in the world, and it is used on corn, the largest crop in the United States. One of the primary targets for atrazine is the weed common groundsel (Senecio vulgaris), the most widespread botanical in the world (Kadereit 1984). As a result of its frequent use, atrazine is the most common contaminant of ground, surface, and drinking water (Aspelin 1994), and its use over the last 40 years has resulted in the evolution of more herbicide-resistant weeds (> 60 species) than any other herbicide (Heap 1997, Gadamski et al. 2003)."

The flowchart below illustrates the EPA registration (approval) process for a new pesticide or a previously registered pesticide having a new ingredient or proposed new use. It appears in the National Institutes of Health 2010 report President’s Cancer Panel-Reports. Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk: What We Can Do Now. Note that the first step in the registration process is “Receives studies from the registrant.”

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN GLYPHOSATE EXPOSURE LIABILITY

University of California (UC) President Janet Napolitano announced in May 2019 a ban on the use of glyphosate on all of UC’s 10 campuses. In announcing the ban, the university cited “concerns about possible human health and ecological hazards, as well as potential legal and reputational risks associated with this category of herbicides.” The UC ban is the latest in a steadily growing avalanche of actions and decisions on glyphosate, the active ingredient in the Monsanto (now owned by Bayer AG) products Roundup and Ranger Pro, and in many other herbicides.

In late March, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors issued a moratorium on the use of glyphosate-based herbicides. The board announced this step citing a need for public health and environmental professionals to determine whether the compound is safe for use, and to explore alternative methods for vegetation management.

On the legal front, three recent and highly publicized court cases have emerged. In addition to the August 2018 landmark decision for the plaintiff in DeWayne Johnson v. Monsanto Company — which case resulted in awards of $39 million in compensation and $250 million in punitive damages — glyphosate has experienced two subsequent defeats in the courts.

In April 2019, a case brought in the District Court for the Northern District of California (in San Francisco), Hardeman v. Monsanto, was decided for the plaintiff, who had developed Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) after 25 years of exposure to Roundup. The jury found that Roundup’s design was defective, the product lacked sufficient cancer warnings, and the manufacturer (Monsanto) had been negligent, awarding the plaintiff $5.3 million in compensation and an additional $75 million in punitive damages.

In mid-May 2019, the Pilliod v. Monsanto case was decided for the plaintiffs, a couple in their seventies who had used Roundup for decades. Four years apart, each of them was diagnosed with NHL, and awards to the plaintiffs in the case amounted to $2.055 billion. Notably, the jury, in a California state court in Alameda, made its decision on the basis of evidence of both glyphosate’s carcinogenicity and Monsanto’s role in suppressing and discrediting independent findings on Roundup’s toxicity.

Approximately 18,000 other glyphosate cases are pending, causing the company’s value to drop by more than 40%. Insurers are starting to recognize the actuarial downsides of underwriting businesses that traffic in glyphosate products. In March 2019, Harrell’s, a major retailer that sells pesticides and other related products in the Midwest, announced it would stop selling glyphosate products because it could not find an insurer to underwrite the company if it kept those items in its product inventory.

REGRETTABLE SUBSTITUTION

Due to the increased awareness of the situation with glyphosate based herbicides, many entities are substituting its use for another synthetic herbicide glufosinate-ammonium. However, the available research shows problematic health effects - meaning we are simply trading six of one for a half dozen of the other.

By using organic landscaping practices we can avoid this game of chemical whack-a-mole and protect public health and the environment from exposure to synthetic pesticides.